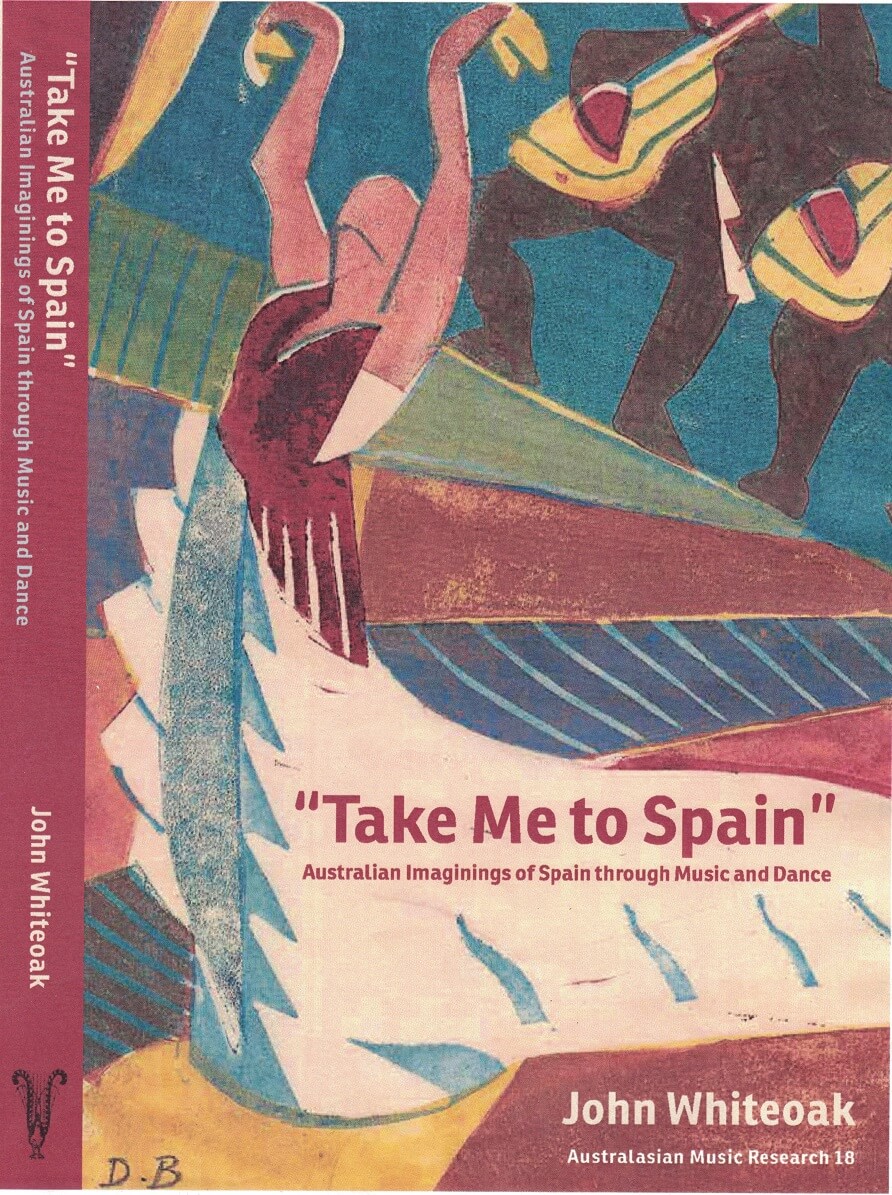

Take Me To Spain

Outline of the concept for the book, its rationale, approach and distinguishing features

Spain, by its very nature, is a flaring honey-flower to the writing bee, pure flame for the moth called Imagination Man (Colin Simpson, Take Me to Spain 1963)

Before ‘flamenco’ song, dance and musical accompaniment as we know them today were developed in Spain, colonial Australian audiences were already being thrilled and sometimes morally outraged by strangely erotic, exciting and rhythmic Spanish dancing in costume to castanets and other appropriately ‘Spanish’ musical accompaniment, and the ‘Spanish guitar’ was already a delicate thread in the fabric of colonial musical entertainment. Furthermore, a remarkably diverse and richly complex Australian history of Spain-themed inflection in music and dance can be traced from the 1820s to the now almost forgotten multi-faceted “flamenco craze” that deeply permeated Australian society and culture in the late 1950s and ‘60s. This craze corresponded with modest migration from Spain, inspirational tours by flamenco theatre companies and gifted individual performers from Spain. Direct Australian engagement with Spanish or Portuguese-speaking people and their music and dance cultures was, however, very minimal before this time, albeit with the significant exceptions that are discussed in this book.

Take Me to Spain is a foundation-research history of the many diverse ways that people living in Australia from early colonial times up to the waning of the late 1950s and 1960s flamenco craze have been “taken” or “transported” in their imagination to an exoticized “Spain” through music and dance. This was music and dance that was, in most cases, the product of creative appropriation by non-Spanish, such as William Wallace’s Spain-themed opera, Maritana or, in the absence of Spanish artists, performed by non-Spanish such as “Lola Montez” and numerous lesser-known figures of colonial and later music and dance history.

This book is therefore also a history of colonial and Twentieth Century Australian perceptions of Spain-themed music and dance and of the mediation, multi-mediation and/or hybridization of music and dance believed (or imagined) to have originated in Spain. The phrase I chose to embody this idea, Take Me to Spain, is the title of a 1963 Australian-authored travel book in my library purchased in London following several early 1960s visits to Spain. The historical data collated for the study has been interpreted via an array of concepts initially conceived for my ongoing Tango Touch publication project, including “retained ethnicity”, “assimilated ethnicity”, “hyper-ethnicity”, “hyper-delineation” and “ethno-mediation” as described at www.ausmdr.com. Take Me to Spain is nevertheless densely descriptive, not densely theoretical. The main distinguishing features of the book are arguably as follows. The concept, scope and approach of the work make it a pioneering study in Australian music, dance and cultural history. It also represents a rare Australian-conceived example of a crossover study in music and dance research, while drawing equally upon popular music studies’ methodology and traditional historical musicology. The foundation research and the concept for the book contribute significantly to Australian dance history research and also provide an expansive history of Spain-related music and dance influences before the late twentieth-century mass migration of Spanish-speaking people enabled them to gain Australian ownership of these influences.

From a global perspective the book contributes to Hispanic studies in a comparable but more modest way than John Storm Roberts’ much-cited The Latin Tinge: The Impact of Latin American Music on the United States (1979) in that it offers a theoretical and structural model for the study of Hispanic-inflected music and dance in other countries where the direct influence of Spanish or Portuguese-speaking practitioners may have been minimal.